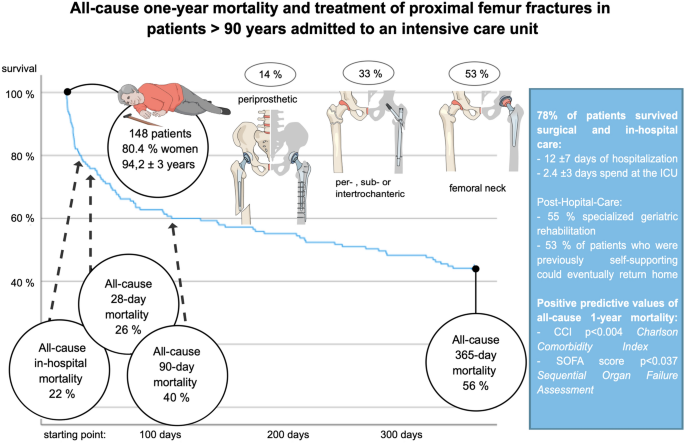

In this large study of 148 very elderly patients ≥ 90 years who underwent surgically treatment for PFFs or periprosthetic femur fractures and were consecutively admitted to the ICU, our main findings were: (A) 78% of patients survived surgical procedure and hospitalization, including ICU treatment; (B) 53% of patients who resided in private dwellings prior to admission were able to return home; and (C) Independent predictors of one-year all-cause mortality included higher CCI and SOFA scores at ICU admission (Fig. 3).

Shown is a concise overview of important study characteristics and results supporting further interpretation.

To our knowledge this is the first comprehensive study focusing on a very vulnerable sub-cohort of very elderly patients with PFFs treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). We found an all-cause in-hospital mortality of 22% and one-year mortality of 56% in the present study. Of interest is, this is twice as high as reported in contemporary European studies of elderly patients with PFFs: In a prospective multicenter study in Spain (997 cases, 2014 – 2016, mean age 84 years) in-hospital and 60-day mortality was reported to be 2 and 11% respectively18. Similarly, in a large German registry study (9780 patients, 2017 – 2019, mean age 84 years) the mortality rate was five percent in-hospital and 12% during their overall 120-day observation period3. International comparison shows a two percent in-hospital mortality in Taiwan (841 cases, 2016 – 2020, mean age 86 years)19 and in Turkey (335 patients, 2017 – 2019, mean age 83 years), short term (30 and 90 days) as well as one-year mortality were ten, twenty-two and 34% respectively20. Turgut et. al identified age > 90 years as independent prognostic risk factor for short and long-term mortality (p = 0.003)20. Focusing on contemporary cohorts composed of nonagenarians, a sub-analysis of the prospective study by Barceló et. al in Spain found in-hospital mortality of thirteen percent and cumulative mortality rates at 30-days, 3-months and 1-year of 20, 31 and 51% respectively (200 cases, 2009—2015, mean age 97 years)18,21. In a Swedish registry 30-day and 1-year mortality was found to be ten and seventeen percent (101, 2008 – 2012, 92 years)22. Internationally, in China two independent studies reported 6-month, 1- and 2-year mortality rates between 7 – 20%, 14 – 30% and 29 – 45% (184/144, 1997 – 2010/2014 – 2018)23,24.

The initially higher mortality rate in our study can be attributed to the specific cohort and institutional factors. First, our study only included patients treated in the ICU, leading to a selection of predominantly critically ill nonagenarians with a higher susceptibility to rapid health deterioration25. This is supported by Turgut et al., who found a significant increase in 30-, 90- and 365-day mortality for both admission to and length of ICU stay in their cohort (ICU admission rate of 55%) through univariate analysis20. Second, our level one trauma and orthopedic department is one of the largest tertiary referral centers in the area, resulting in the transfer of complex cases into our care, but also more frequent admission of critically ill patients to our emergency unit26. Additionally, our university medical center commonly treats patients with severe co-morbidities, including fall-related PFFs due to oncologic health issues, which implies the presence of serious underlying health issues. In conclusion, our study cohort is reflective of a typical contemporary PFF cohort of nonagenarians at a tertiary trauma and orthopedic center.

As life expectancy increases worldwide, a growing number of individuals reaching the mile stone of 90 years, are expected to live for several more years. According to the German federal statistical office (DESTATIS) and the human mortality database report, in 2020, the average mortality rate for German individuals aged 94 (which aligns with the median age of the sample cohort) was reported to be 27%27,28. In contemporary cohorts of nonagenarians, all-cause one-year mortality rates were found to be 20% (Italy, n = 433, median age of 92), 19% (Spain, n = 186, mean age of 93), and 26% (Danish cohort of 1905, n = 579, at time of analysis 93 years)29,30,31. Comparatively, admission with a PFF and consecutive ITS admission increases the risk of mortality twofold when compared to the general population, emphasizing the need for further understanding of specific risk factors in this vulnerable patient group. Calculations for the birth cohort of 2020 predict a mortality rate of 10 – 17% for men at age 94, which translates to a life expectancy of 4 – 5 more years, and an 8 – 14% mortality rate for women, which translates to life expectancy of 5 – 6 more years27,28. An aging population seeking disability-free years challenges the existing healthcare systems. Preparation to allow efficient and optimal geriatric care will be crucial in reducing morbidity and improving the quality of life for older individuals in the future.

Several comorbidities and patient characteristics have previously been linked to increased mortality after PFFs, including male gender, dementia, cardiac disease, and renal dysfunction26,32,33. However, our study found no significant association between mortality and male gender, COPD, or chronic lung disease. Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis of initially significant values showed that creatinine, lactate, vasopressor dependency, paCO2, signs of chronic kidney failure, heart rate, and mean arterial pressure at ICU admission did not independently predict one-year mortality. The relationship between comorbidities, laboratory results, and mortality remains controversial, with some studies finding significance but lacking further multivariable regression analysis20,22,34. Our study found no increased mortality with out-of-hours surgery compared to previous reports35.

The increase in ICU admissions in recent time seems to be attributed to the heightened concern surrounding unplanned ICU admissions after transferring patients to the surgical ward, a circumstance associated with elevated postoperative morbidity and mortality rates36,37. More than half of the cohorts’ patients received treatment during nonstandard hours, which is linked to reduced staff availability on general wards38. Acknowledging the significance of postoperative care, the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland recommends a 1:4 nurse-to-patient ratio for optimal care when transferred to surgical wards39. Given the vulnerability of this elderly patient cohort and consequently high environment requirements, we suspect that the rising ratio of ICU-treated patients results from a more cautious approach, coupled with an increased availability of intermediate and high care capacity, rather than specific patient criteria.

While 78% of patients survive initial in-hospital treatment, nonagenarians face a higher mortality rate during follow-up with only 44% survival. An Italian cohort study of hospitalized nonagenarian patients (n = 124, median age of 93) showed a similar probability of being alive at one year (45%)40. Over 50% of patients aged 85 and older are considered frail, making them more susceptible to stressors due to limited resources25. Geriatric specialists support our hospital team to assess and monitor nonagenarian patients to minimize adverse events. Despite this, PFFs result in a permanent reduction in quality of life, with a high proportion of patients moving to nursing homes and losing their independence3,8. Studies reported that approximately one out of six patients who lived in a home-dwelling location before the trauma had to be permanently relocated into a nursing facility3,41. In our cohort, half of the patients who previously lived alone were unable to return home, causing a financial and psychological burden on patients and their families. Our ICU setting offers immediate and early physiotherapy which is continued on surgical wards to mobilize patients. This treatment strategy of early and daily rehabilitation was associated with higher discharge rates to private homes in a study in Finland42.

Assessing patient risk after admission for PFFs is crucial in predicting adverse events and complications and guiding patients and their families. This is especially important in critical illness cases requiring ICU treatment. PFFs and their aftermath can cause significant psychological stress, particularly when family members are required to make decisions in cases of rapidly declining health or dementia. Identifying factors that support informed decision-making and accurate assessment of the situation is essential in guiding patients, families, and determining appropriate treatment and care. Of interest is, that patients had only a low number of advance directives which is in line with previous studies in the intensive care setting43. However, in general early discussion of the patient’s concrete wishes should be encouraged to ensure that treatment aligns with the patient’s values, beliefs, and preferences.

-

The SOFA score demonstrated independent predictive value for one-year mortality (p 0.037) in our cohort, with a range of 0 – 12 and mean value of 3.5 ± 3.2 for the MG and 2.1 ± 2.5 for the SG. Although initially designed for patients with sepsis, recent data suggests similar accuracy in both surgical and non-surgical subjects16. Clearly, ICU mortality is strongly associated with organ failure rate and severity which is tied to the SOFA score. A total SOFA score ≤ 4 indicates a high likelihood of discharge without adverse events, while a score ≥ 10 is associated with increased mortality. However, the range between these thresholds provides less precise discrimination, limiting the use of the SOFA score as a prognostic marker. A total SOFA score ≤ 4 indicates a high likelihood of discharge without adverse events, while a score ≥ 10 is associated with increased mortality. However, the range between these thresholds provides less precise discrimination, limiting the use of the SOFA score as a prognostic marker44. In a nutshell, it is clear that organ failure is associated with mortality, however, the lack of adequate discrimination at intermediate SOFA score values makes it an unreliable predictor of mortality44. The interpretation of the SOFA score should be based on its intended use, whether it is as a diagnostic tool, prognostic marker, or resource allocation aid. While it can provide valuable insight into patient severity and potential outcome, it should not be solely relied upon for prognostication. It can also aid in patient triaging and facilitate end-of-life discussions with families44.

-

CCI has been found to have a significant predictive value for mortality after one year (p 0.004). In the study cohort, the mean value was 1.9 ± 1.6 in the one-year MG and 0.09 ± 1 for the SG. With an aging population, hospitals are facing an increase of patients with PFFs and multiple comorbidities, but ICU treatment also allows more critically ill patients to receive surgical care. Recent studies have shown that CCI can accurately predict short-term and in-hospital mortality in PFF patients14,45. Comorbidities in patients with hip fracture have been shown to increased 30-day postoperative mortality46. Schrøder et. al highlighted a comorbidity-related disparity of quality of in-hospital care which unintendedly led to an impaired patient prognosis. Such patients were less likely to receive the totality of recommended care, and rehabilitation with early preoperative optimization and mobilization impacted most47. The level of care dependency was found to be a determinant of quality of life and also of survival rates among comorbid patients with COPD, chronic heart failure or chronic renal failure48. The impact of comorbidities on receiving total recommended care is not limited to patients with PFF, and should be used to highlight the need for tailored clinical initiatives to ensure optimal patient care and best chances of survival47.

This study presents both strengths and limitations. Although the sample size is limited, it is the first extensive examination of the incidence of mortality among critically ill nonagenarians with PFFs. The single-center design restricts the generalizability to other healthcare settings, such as non-tertiary level hospitals. We acknowledge the disparities observed across nations which are shaped by diverse healthcare infrastructures, economic capacities, and cultural contexts and are often intertwined with the availability and allocation of resources. These differences underscore the importance of considering the resource landscape when interpreting and comparing outcomes on a global scale. To increase significance, it is recommended to validate the findings using a separate cohort in future studies. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the study and its focus on the ICU perspective restricts the available data on preoperative functional values, and there may be other influential factors impacting mortality that were not considered in this study. Also, only restricted demographic data regarding non-ICU admitted and conservatively treated patiens were available for analysis.

link